The story of energy and the economy seems to be an obvious common sense one: some sources of energy are becoming scarce or overly polluting, so we need to develop new ones. The new ones may be more expensive, but the world will adapt. Prices will rise and people will learn to do more with less. Everything will work out in the end. It is only a matter of time and a little faith. In fact, the Financial Times published an article recently called “

Looking Past the Death of Peak Oil” that pretty much followed this line of reasoning.

Energy Common Sense Doesn’t Work Because the World is Finite

The main reason such common sense doesn’t work is because in a finite world, every action we take has many direct and indirect effects. This chain of effects produces connectedness that makes the economy operate as a network. This network behaves differently than most of us would expect. This networked behavior is not reflected in current economic models.

Most people believe that the amount of oil in the ground is the limiting factor for oil extraction. In a finite world, this isn’t true. In a finite world, the limiting factor is feedback loops that lead to inadequate wages, inadequate debt growth, inadequate tax revenue, and ultimately inadequate funds for investment in oil extraction. The behavior of networks may lead to economic collapses of oil exporters, and even to a collapse of the overall economic system.

An issue that is often overlooked in the standard view of oil limits is diminishing returns. With diminishing returns, the cost of extraction eventually rises because the easy-to-obtain resources are extracted first. For a time, the rising cost of extraction can be hidden by advances in technology and increased mechanization, but at some point, the inflation-adjusted cost of oil production starts to rise.

With diminishing returns, the economy is, in effect, becoming less and less efficient, instead of becoming more and more efficient. As this effect feeds through the system, wages tend to fall and the economy tends to shrink rather than grow. Because of the way a networked system “works,” this shrinkage tends to collapse the economy. The usage of energy products of all kinds is likely to fall, more or less simultaneously.

In some ways current, economic models are the equivalent of flat maps, when we live in s spherical world. These models work pretty well for a while, but eventually, their predictions deviate farther and farther from reality. The reason our models of the future are wrong is because we are not imagining the system correctly.

The Connectedness of a Finite World

In a finite world, an action a person takes has wide-ranging impacts. The amount of food I eat, or the amount of minerals I extract from the earth, affects what other people (now and in the future) can do, and what other species can do.

To illustrate, let’s look at an exaggerated example. At any given time, there is only so much broccoli that is ready for harvest. If I decide to corner the broccoli market and buy up 50% of the world’s broccoli supply, that means that other people will have less broccoli available to buy. If those growing the broccoli spray the growing crop with pesticides, “broccoli pests” (caterpillars, aphids, and other insects) will die back in number, perhaps contributing to a decline of those species. The pesticides may also affect desirable species, like bees.

Growing the broccoli will also deplete the soil of nutrients. If 50% of the world’s broccoli is shipped to me, the nutrients from the soil will find their way around the world to me. These nutrients are not likely to be replaced in the soil where the broccoli was grown without long-distance transport of nutrients.

To take another example, if I (or the imaginary company I own) extract oil from the ground, the extraction and the selling of that oil will have many far-ranging effects:

- The oil I extract will most likely be the cheapest, easiest-to-extract oil that I can find. Because of this, the oil that is left will tend to be more expensive to extract. My extraction of oil thus contributes to diminishing returns–that is, the tendency of the cost of oil extraction to rise over time as resources deplete.

- The petroleum I extract from the ground will consist of a mixture of hydrocarbon chains of varying lengths. When I send the petroleum to a refinery, the refinery will separate the petroleum into varying length chains: short chains are gasses, longer chains are liquids, still longer ones are very viscous, and the longest ones are solids, such as asphalt. Different length chains are used for different purposes. The shortest chains are natural gas. Some chains are sold as gasoline, some as diesel, and some as lubricants. Some parts of the petroleum spectrum are used to make plastics, medicines, fabrics, and pesticides. All of these uses will help create jobs in a wide range of industries. Indirectly, these uses are likely to enable higher food production, and thus higher population.

- When I extract the oil from the ground, the process itself will use some oil and natural gas. Refining the oil will also use energy.

- Jobs will be created in the oil industry. People with these jobs will spend their money on goods and services of all sorts, indirectly leading to greater availability of jobs outside the oil industry.

- Oil’s price is important. The lower the price, the more affordable products using oil will be, such as cars.

- In order for consumers to purchase cars that will operate using gasoline, there will likely be a need for debt to buy the cars. Thus, the extraction of oil is tightly tied to the build-up of debt.

- As an oil producer, I will pay taxes of many different types to all levels of governments. (Governments of oil exporting countries tend to get a high percentage of their revenue from taxes on oil. Even in non-exporting countries, taxes on oil tend to be high.) Consumers will also pay taxes, such as gasoline taxes.

- The jobs that are created through the use of oil will lead to more tax revenue, because wage earners pay income taxes.

- The government will need to build more roads, partly for the additional cars that operate on the roads thanks to the use of gasoline and diesel, and partly to repair the damage that is done as trucks travel to oil extraction sites.

- To keep the oil extraction process going, there will likely need to be schools and medical facilities to take care of the workers and their families, and to educate those workers.

Needless to say, there are other effects as well. The existence of my oil in the marketplace will somehow affect the market price of oil. Burning of the oil may affect the climate, and will tend to acidify oceans. It would be possible to go on and on.

The Difficulty of Substituting Away from Oil

In some sense, the use of oil is very deeply imbedded into the operation of the overall economy. We can talk about electricity replacing oil, but oil’s involvement in the economy is so pervasive, it can’t possibly replace everything. Perhaps electricity might replace gasoline in private passenger automobiles. Such a change would reduce the demand for hydrocarbon chains of a certain length (C7 to C11), but that only reduces demand for one “slice” of the oil mixture. Both shorter and longer chain hydrocarbons would be unaffected.

The price of gasoline will drop, (making Chinese buyers happy because more will be able to afford to use motorcycles), but what else will happen? Won’t we still need as much diesel, and as many medicines as before? Refiners can fairly easily break longer-chain molecules into shorter-chain molecules, so they can make diesel or asphalt into gasoline. But going the other direction doesn’t work well at all. Making gasoline into shorter chains would be a huge waste, because gasoline is much more valuable than the resulting gases.

How about replacing all of the taxes directly and indirectly related to the unused gasoline? Will the price of electricity used in electric-powered vehicles be adjusted to cover the foregone tax revenue?

If a liquid substitute for oil is made, it needs to be low priced, because a high-priced substitute for oil is very different from a low-priced substitute. Part of the problem is that high-priced substitutes do not leave enough “room” for taxes for governments. Another part of the problem is that customers cannot afford high-priced oil products. They cut back on discretionary expenditures, and the economy tends to contract. There are layoffs in the discretionary sectors, and (again) the government finds it difficult to collect enough tax revenue.

The Economy as a Networked System

I think of the world economic system as being a networked system, something like the dome shown in Figure 1. The dome behaves as an object that is different from the many wooden sticks from which it is made. The dome can collapse if sticks are removed.

The world economy consists of a network of businesses, consumers, governments, and resources that is bound together with a financial system. It is self-organizing, in the sense that consumers decide what to buy based on what products are available at what prices. New businesses are formed based on the overall environment: potential customers, competition, resource availability, services available from other businesses, and laws. Governments participate in the system as well, building infrastructure, making laws, and charging taxes.

Over time, all of these gradually change. If one business changes, other business and consumers are likely to make changes in response. Even governments may change: make new laws, or build new infrastructure. Over time, the tendency is to build a larger and more complex network. Unused portions of the network tend to wither away–for example, few businesses make buggy whips today. This is why the network is illustrated as hollow. This feature makes it difficult for the network to “go backward.”

The network got its start as a way to deliver food energy to people. Gradually economies expanded to include other goods and services. Because energy is required to “do work,” (such as provide heat, mechanical energy, or electricity), energy is always central to an economy. In fact, the economy might be considered an energy delivery system. This is especially the case if we consider wages to be payment for an important type of energy–human energy.

Because of the way the network has grown over time, there is considerable interdependency among different types of energy. For example, electricity powers oil pipelines and gasoline pumps. Oil is used to maintain the electric grid. Nuclear electric plants depend on electricity from the grid to restart their operations after outages. Thus, if one type of energy “has a problem,” this problem is likely to spread to other types of energy. This is the opposite of the common belief that energy substitution will fix all problems.

Economies are Prone to Collapse

We know the wooden dome in Figure 1 can collapse if “things go wrong.” History shows that many civilizations have collapsed in the past. Research has been done to see why this is the case.

Joseph Tainter’s research indicates that diminishing returns played an important role in the collapse of past civilizations. Diminishing returns would be a problem when adding more workers didn’t add a corresponding amount more output, particularly with respect to food. Such a situation might be reached when population grew too large for a piece of arable land. Degradation of soil fertility might play a role as well.

Today, we are reaching diminishing returns with respect to oil supply, as evidenced by the rising cost of oil extraction. This is occurring because we removed the easy to extract oil, and now must move on to the more expensive to extract oil. In effect, the system is becoming less efficient. More workers and more resources of other types are needed to produce a given barrel of oil. The value of the barrel of oil in terms of what it can do as work (say, how far it can move a car, or how much heat it can produce) is unchanged, so the value each worker is producing is less. This is the opposite of efficiency.

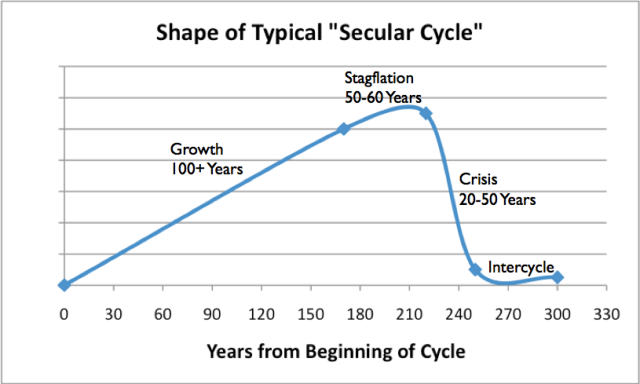

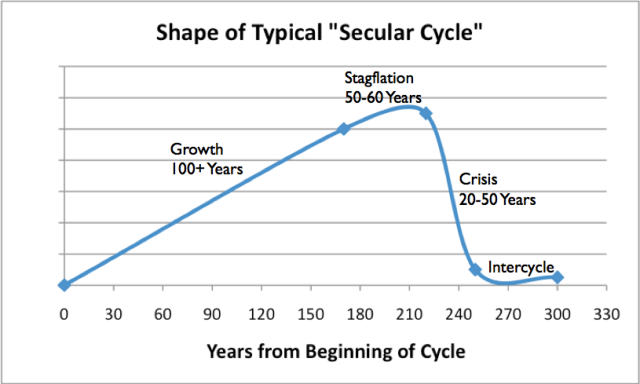

Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov have done research on the nature of past collapses, documented in a book called

Secular Cycles. An economy would clear a piece of land, or discover an approach to irrigation, or by some other means discover a way to expand the number of people who could live in an area. The resulting economy would grow for well over 100 years, until population started catching up with resource availability. A period of stagflation followed, typically for about 50 or 60 years, as the economy tried to continue to grow, but bumped against increasing obstacles. Wage disparity grew as wages of new workers lagged. Debt also grew.

Eventually collapse occurred, over a period of 20 to 50 years. Often, much of the population died off. An inter-cycle period followed, during which resources regenerated, so that a new civilization could arise.

Figure 2. Shape of typical Secular Cycle, based on work of Peter Turkin and Sergey Nefedov in

Secular Cycles.

One of the major issues in past collapses was difficulty in funding government services. Part of the problem was that wages of common workers were low, making it difficult to collect enough taxes. Part of governments’ problems were that their costs went up, as they tried to solve the increasingly complex problems of society. Today these costs might include unemployment insurance and bailing out banks; in ages past they included larger armies to try to conquer new lands with more resources, as their own resources depleted.

Today’s Situation

Our situation isn’t too different. The economy started growing in the early 1800s, abut the we started using fossil fuels, thanks to technology that allowed us to use them. Oil is the fossil fuel that is depleting most quickly, because it is very valuable in many uses, including transportation, agriculture, construction, mining, and as a raw material to produce many goods we use every day.

Our economy seems to have hit stagflation in the early 1970s, when oil prices first began to spike. Now, some of the symptoms we are seeing are looking distressingly like the symptoms that other civilizations saw prior to the beginning of collapse. Our networked system has many weak points:

- Oil exporters Governments can collapse, as the government of the Former Soviet Union did in 1991, if oil prices are too low. The fact that oil prices have not risen since 2011 is probably contributing to unrest in the Middle East.

- Oil importers Spikes in oil prices lead to recession.

- Governments funding Debt keeps expanding; infrastructure needs fixes but they don’t get done; too many promises for pensions and healthcare.

- Failing financial systems Debt defaults are likely to be a major problem if the economic system starts shrinking. Debt is needed to keep oil prices up.

- Contagion if one energy product is in short supply This happens many ways. For example, nearly all businesses rely on both electricity and oil. If either one of these becomes unavailable (say oil to supply parts and ship goods to customers), then the business will need to close. Because of the business closure, demand for other energy products the business uses, such as electricity and natural gas, will drop at the same time. Direct use of energy products to produce other energy products (mentioned previously) also contributes to this contagion.

Unfortunately, when it comes to operating an economy, it is

Liebig’s Law of the Minimum that rules. In other words, if any required element is missing, the system doesn’t work. If businesses can’t get financing, or can’t pay their employees because banks are closed, businesses may need to close. Workers will get laid off, and the

inability to afford energy products (economists would call this “lack of demand”) will be what brings the system down.

Modeling our Current Economy

Everywhere we look, we see models of how the energy system or the economy can be expected to work. None of the models match our current situation well.

Growth will Continue As in the Past It is pretty clear that this model is inadequate. Every

revision to growth estimates seems to be downward. In a finite world, we know that growth at the same rate can’t continue forever–we would run out of resources, and places for people to stand. The networked nature of the system explains how the system really grows, and why this growth can’t continue indefinitely.

Rising Cost of Producing Energy Products Doesn’t Matter In a global world, we compete on the price of goods and services. The cost of producing these goods and services depends on (a) the cost of energy products used in making these goods and services (b) wages paid to workers for producing these services (c) government, healthcare, and other overhead costs, and (d) financing costs.

One part of our problem is that with globalization, we are competing against warm countries–countries that receive more free energy from the sun than we do, so are warmer than the US and Europe. Because of this free energy from the sun, homes do not need to be built as sturdily and less heat is needed in winter. Without these costs, wages do not need to be as high. These countries also tend to have less expensive healthcare systems and lower pensions for the elderly.

Governments can try to fix our non-competitive cost structure compared to these countries by reducing interest rates as much as possible, but the fact remains–it is very difficult for countries in cold parts of the world to compete with countries in warm parts of the world in making goods. This cost competition problem becomes worse, as the price of energy products rises because we are competing with a cost of $0 for heating requirements. If cold countries add carbon taxes, but do not surcharge goods imported from warm countries, the disparity with warm countries becomes even worse.

In the early years of civilization, warm countries dominated the world economy. As energy prices rise, this situation is likely to again occur.

Price is Not Important Apart from the warm country–cool country issue, there is another reason that energy cost (in real goods, not just in financial printed money) is important:

The price of the energy used in the economy is important because it is tied to how much must be “given up” to buy the oil or anther energy product (such as food). If energy is cheap, little needs to be given up to obtain the energy. Because of energy’s huge ability to do “work,” the work that is obtained can easily make goods and services that compensate for what has been given up. If energy is expensive, there is much less benefit (or perhaps negative benefit) when what is given up is compared to the work that the energy product provides. As a result, economic growth is held back by high-priced energy products of any kind.

Supply and Demand Leads to Higher Prices and Substitutes Major obstacles to the standard model working are (a) diminishing returns with respect to oil supply, (b) recession and even government failure of oil importers, when oil prices rise and (c) civil unrest and even government failure in oil exporters, if oil prices don’t keep rising. If there isn’t enough oil supply, oil prices rise, but there are soon so many follow-on effects that oil prices fall back again.

Reserves/ Production This ratio supposedly tells how long we can produce oil (or natural gas or coal) at current extraction rates. This ratio is simply misleading. The real limit is how long the economy can function, given the feedback loops related to diminishing returns. If a person simply looks at investment dollars required, it becomes clear that this model doesn’t work. See my post

IEA Investment Report – What is Right; What is Wrong.

Energy Payback Period, Energy Return on Energy Invested, and Life Cycle Analysis These approaches look at the efficiency of energy production, comparing energy used in the process to energy produced in the process. In some ways, they work–they show that we are becoming less and less efficient at producing oil, or coal, or natural gas, as we move to more difficult to extract resources. And they can be worthwhile, if a decision is being made as to which of two similar devices to purchase: Wind Turbine A or Wind Turbine B.

Unfortunately, modeling a finite world is virtually impossible. These approaches use narrow boundaries–energy used in pulling oil out of the ground, or making a wind turbine. It doesn’t tell as much as we need to know about new energy generation equipment, together with (a) changes needed elsewhere in the system and (b) whatever financial system is used to pay for the energy generated with that system, will actually work in the economy. To really analyze the situation, broader analyses are needed.

Furthermore, there are the inherent assumptions that (a) we have a long time period to make changes and (b) one energy source can be substituted for another. Neither of these assumptions is really true when we are this close to oil limits.

Where the Peak Oil Model Went Wrong

Part of the Peak Oil story is right: We are reaching oil limits, and those limits are hitting about now. Part of the Peak Oil story is not right, though, at least in a common version that is prevalent now. The version that is prevalent is more or less equivalent to the “standard” view of our current situation that I talked about at the beginning of the post. In this standard view, oil supply will not disappear very quickly–approximately 50% of the total amount of oil ever extracted will become available after the peak in oil production. There will be considerable substitution with other fuels, often at higher prices. The financial system may be affected, but it can be replaced, and the economy will continue.

This view is based on writing of M. King Hubbert

back in 1957. At that time, it was commonly believed that nuclear energy would provide electricity

too cheap to meter. In fact, in a

1962 paper, Hubbert talks about “reversing combustion,” to make liquid fuels. Thus, not only did his story include cheap electricity, it also included cheap liquid fuels, both in huge quantity.

In such a situation, growth could continue indefinitely. There would be no need to replace huge numbers of vehicles with electric vehicles. Governments wouldn’t have a problem with funding. There would be no problem with collapse. The supply of oil and other fossil fuels could decline slowly, as suggested in his papers.

But the story of the cheap, rapid nuclear ramp-up didn’t materialize, and we gradually got closer to the time when limits were beginning to hit. Major changes were needed to Hubbert’s story to reflect the fact that we really didn’t have a fix that would keep business as usual going indefinitely. But these changes never took place. Instead the view of how little change was needed to keep the economy going kept getting downgraded more and more. “Standard” economic views filtered into the story, too.

There is a correct version of the oil limits story to tell. It is the story of the failure of networked systems.